Community researcher – Rachel Harriss

In 1841, the area now covered by Dinham Road was subdivided between 6 different landowners with a lane surrounded by orchard, pasture and gardens. The two front plots, on the slope immediately adjacent to the Iron Bridge and on the other side St David’s Hill, had a number of close-knit houses and an area of waste disposal.

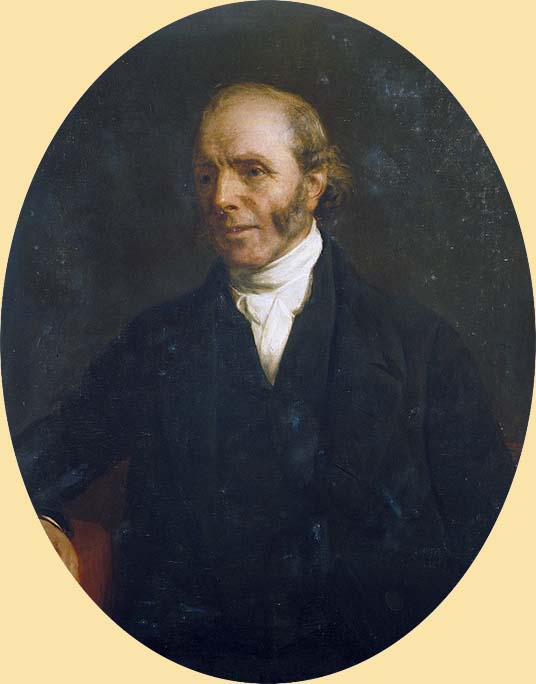

The road took its name from John Dinham, tea merchant and benefactor. He purchased the land at the far end of the lane, on the high plateau above the Exe, and paid for forty-eight free cottages for elderly people. They opened in 1862. The area was enhanced further when another benefactor, wealthy merchant and shipper William Gibbs, paid for the construction of St Michael’s and All Angels Church and then later St David’s National Boys School which opened in 1868.

The houses date from the late 1800s. The eight buildings which make up Churston Terrace had been built from 1864. In 1871 the heads of the households included a retired jeweller, gardener, ironmonger, draper’s traveller and an annuitant or pensioner.

Dinham Road was named in about 1879 and two years later the census listed six houses. The development continued: a stone plaque on the front of number 5 declares “Mount Dinham Villas 1887”. Numbers 1 to 3 were lost to bomb damage but Numbers 4 to 6 remain; these are large double fronted houses each with bays and two attic rooms.

It was a time of rapid expansion in house-building and there would have been plentiful work for skilled tradespeople in fitting out new homes. In 1881, Number 2 was occupied by Shadrack Newcombe, carpenter and joiner, and his wife Sarah, a purchaser of wardrobes. Head of the household at Number 4 was William Rice, a plumber, whilst Number 5 was occupied by John Elliott, a coal merchant, who had moved to Exeter from Brixham. Lodgers lived alongside each of these family units; Mr E. Happerfield at Number 4 was a cooper at St Anne’s Brewery and Number 5 gave boarding to a lath renderer.

By this date the substantially-built houses had begun to attract families with young children, some Exeter born, but significant numbers came from elsewhere in Devon and further afield. Number 2 was occupied by Alfred Ward, a printer compositor, his wife and two young children, Number 6 by William Guest, a furniture broker, and his three children, and Number 7 by Herbert Keeping, a woollen draper’s assistant, and his three young children.

The houses continued to provide board and lodgings for engine fitters, watchmakers, drapers and grocers. The households had also started to afford servants, with Numbers 1, 4, 6 and 7 listing domestic helpers for the first time.

Other occupations find their way in to the census at this point too; at Number 3, William Finch is listed as a letter carrier for the GPO and at Number 4, Henry Bartlett was a pianoforte dealer and his wife, a teacher of music.

Ownership of a piano and an ability to play was a symbol of social status amongst the growing middle classes.

Skilled crafts people continued to be the mainstay of the road; Number 5 was the home of George Bradbeer, a builder, his three adult sons, all joiners and his three daughters all dressmakers. Number 9 meanwhile was occupied by a William E. Hart, a potter and manager of the Messrs Cole and Trelease’s Exeter Art Pottery situated at 7 Exe Street. Hart, his wife and 6 children had moved from the Aller Vale pottery at Newton Abbot where he was foreman. Lodging with them were his niece Lily, a shop maid at the Art Pottery. A new showroom had been opened at 1, Luxury Lane, off Bonhay Road, in March 1891. The other lodgers were Herbert E. Bulley, a potter, and Charles Collard, a pottery decorator, who had been born in Torquay.

Dinham Road in the early 1900s

Growing numbers of tourists visiting coastal resorts by train had begun to provide a ready market for souvenirs and art pottery and emerging industries were also often in search of promotional gifts. Designs were painted on plates, egg cups, ashtrays and decorative jugs. In 1893 Hart was joined by Bovey Tracey born and trained Alfred Moist who had been working in Gloucester as a potter. They purchased a field and a cob barn at Haven Road and went on to establish Hart and Moist, the Devon Art Pottery, which received wide acclaim. The height of their production was in 1894 when they exhibited at the Devon County Show; a report recorded that they showed 184 shapes and designs in numerous colours. Life for the Hart family in Exeter had begun at 9 Dinham Road, but it must have been a full house and by 1892 they had moved to 8, West View Terrace, just off Exe Street and very close to the pottery.

Numbers 12 to 18 had been built by the time the census enumerator visited in 1901. Numbers 12 to 15 were substantial houses following a pattern of a single bay window on each level and an attic room. Numbers 16 to 18 were built to a different style without attic rooms and they have a central doorway and double front.

Skilled craftspeople continued to occupy many of the houses. In Number 4 was Charles Webber, an employer in the woodturning trade. His two sons Arthur and Frank were in the same business. Number 8 housed an apprentice woodcarver, William Stone.

Dressmaking and millinery were also significant occupations employing no fewer than five of the unmarried females resident in the road at this time. The sewing machine had become widely available in the UK in the late nineteenth century and propelled the clothing industry into one of mass production.

Tailors and tailoresses were often paid by piecework and working from home was common. The workers hired a sewing machine to finish ready-to-wear garments. The work, although often poorly paid, was often essential to maintain the family income.

St David’s School had been founded in 1868 and it is likely the teachers lived locally. Number 8 was occupied by Mary Fitzgerald, a school governess, and Amelia Stone, a schoolteacher and her sister, Sophia, a sixteen-year-old pupil schoolteacher. Next door at Number 9, Charles Munday, a boarder, was also a pupil schoolteacher. Head of the household at Number 16 was Harry Gater, also a schoolteacher. By 1911 he had moved to Number 8 and is listed as Assistant School Master at St David’s School, later moving again to 40 St David’s Hill.

Resident at Number 15 was John Compton, a Salvation Army preacher. He gives his birthplace as Norfolk and that of his wife Elizabeth as Yorkshire and their children had been born in Canada. They employed a domestic servant, Florence Selland, as did those living in the other larger double fronted houses, Numbers 4 and 5.

In 1911, the census recorded that the street was once again occupied by a number of families with younger children. Skilled manual trades continued to be the occupation of many of the heads of household. Number 1 was occupied by a boot-maker and dealer and Number 5 by an upholsteress. The railway also continued to be an employer; George Roberts at Number 9 was a Foreman Shunter with G.W.R and Benjamin Boucher at Number 12, was a ticket collector.

Meanwhile at Number 13, Frederick Forward and one of his sons were piano and organ tuners; another reflection of the Victorian middle-class fashion for home ownership of a piano. In the 1870s music had been added to the curriculum at the School for the Blind around the corner and many pupils learnt to use a specially developed, raised music notation. Some even went on to become piano tuners and it is just possible there was some connection between the school and the Forwards.

The Forwards were a large family including seven sons, Frederick, Frank, William, Charles, Henry, Edward (died aged 11), and Leonard. Frederick Senior received a letter from King George V when his five older boys were on active service in the Great War.

He was the foremen of works for John C. Guest, an owner of music shops in the High Street and Bridge Street. His youngest son Leonard learnt his trade as a piano tuner with the Guest company and started his own business repairing and selling pianos in Sidwell Street opposite the Odeon. His shop was bombed during the Blitz in 1942. He played violin at the Mint Methodist Church in Fore Street. Leonard Forward subsequently bought Number 9 and let the bottom and top floors to tenants.

Dinham Road in the second world war

The 1939 Register continues to show residents were employed by the railway industry. Edward Parsons at Number 5 was a railway shed labourer, George Denning at Number 6 was a railway timekeeper and Henry Bagwell at Number 11 was a railway goods guard.

Significantly a number of blind people were also listed as resident in the street. In 1843 the West of England Institute for the Instruction and Employment of the Blind had moved to the building now occupied by the Community Centre on St David’s Hill. The school prospered and by 1930 there were 188 blind persons registered, of which 73 were elementary pupils, 8 technical pupils, 20 workshop employees, 50 home workers and 4 with other employment. In 1939, Number 4 Dinham Road was providing a home for both Annie Stannard and Mary Farrell who are recorded as ‘Machinists (Blind)’ and Arthur

Holloway, resident at Number 14, was also recorded as blind. At the outbreak of the war multiple occupation was still a feature of many households. Henry Bagwell and his family, living at Number 11, were joined by Evelyn Mottershead, shorthand typist and ARP warden, William Brownsell (furniture warehouseman), Audrey Wills (insurance shorthand typist) and Edwin Letheren, (retired ecclesiastical sculptor).

James Bell recalled a resident of Dinham Road who worked at the Boy’s Episcopal School: ‘There was Alfie Webster, the caretaker, who was the headmaster’s pet and spy – he would report you for breaking school rules. As a result he got a hard time from the boys. Alfie Webster also had a newsagent and tobacconist on the corner of Dinham Road. At the end of each day we had to put our chairs on the desks so that he could sweep the classroom. We put all the chairs just on the edge and one touch of his broom and they would all fall down like dominoes.

The school had a large coke boiler, and when there was a delivery of coke, Alfie went down to the boiler room to shovel the coke away from the bottom of the chute as it came down. The boys blocked the entrance with a blank and only pulled it away when there was a huge pile. There was a rush of coke, it buried Alfie, he came up the steps gasping for breath and black as coal – he was met by the boys’ jeers, one up to us!’

During the Second World War Alfred Webster and his wife lived above the premises on the corner of Dinham Road and St David’s Hill. On the night of 3 May 1942, in retaliatory action after the Baedeker raids, a large German firebomb was dropped on the corner of the road adjacent to the Iron Bridge. Numbers 1 to 3 Dinham Road were lost as were Numbers 7 to 8 and there was quite possibly loss of life. It was an incident that changed the look of the street forever.