Community researcher – Hannah Singleton

Cholera reached Exeter in July 1832, brought into the city from Plymouth by a young mother and her children residing in North Street. Fear of cholera had been prevalent since 1818 when there was an outbreak in India. A second wave started in 1826, reached Europe in 1830 and in the autumn of 1831 an outbreak in Sunderland signalled its arrival in England. Exeter had been preparing for an outbreak for some time but had not taken a very rigorous approach.

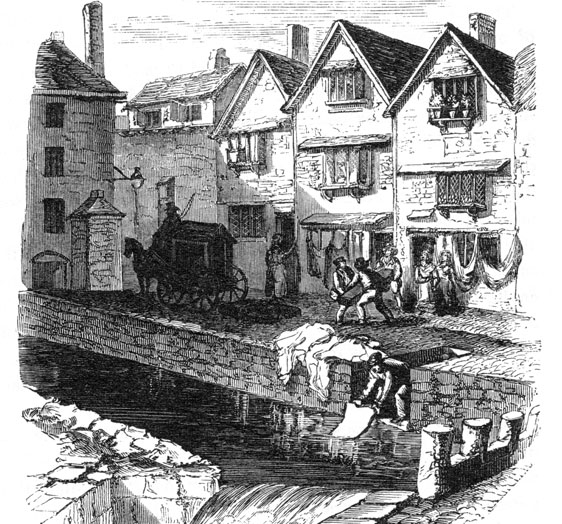

A Board of Health was set up which included representatives from the Corporation for the Poor and the Commissioners of Improvement to prepare for the outbreak. They aimed to cleanse open drains, install sewers and provide water for street cleansing. Many of the poorest parts of the city were knee deep in rubbish and many did not have access to sufficient water. There were not enough wells and those that existed had fallen into disrepair.

The official city supply of water did not service all of Exeter and, in any case, many could not afford the water it provided. The head of the private water company made efforts to clean more streets and supply more households with water but it was acknowledged that the supply was not fit for purpose. It was acknowledged that the situation had to be rectified and the water supply was subsequently overhauled.

Exeter suffered a shorter outbreak than other parts of the country. Of the population of 32,000, including those living in St Thomas, 1,400 fell ill and 440 died. Most were from the poorer south-west parts of the city and 48 were from St Thomas.

The Cholera epidemic and the inhabitants of St David’s

The cholera epidemic caused great anxiety amongst the parishioners of St David’s. The Board of Health had suggested that the field of Bury Meadow was suitable ground for a cholera burial site for the city. Bury Meadow had been leased out to various landowners in the previous years. The first mention of the land in local newspaper reports was in 1806. It also seems to have been used by parishioners for more recreational uses as there was a report of a ‘regular’ fight held there in 1829 by the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette involving two teenage boys. This is the only instance that was reported on, so how often events like these occurred is unknown.

The parishioners protested that the land was not consecrated and, furthermore, they did not wish to have the dead from other parishes buried in St David’s.

In July, when the initial order was given for the burial ground to be used, they attacked the gravedigger employed to dig the grave for a cholera victim, and several kept watch in the Warden’s house over night to ensure the burial did not continue.

The chairman of the Board of Health wrote to the Bishop of Exeter asking him to consecrate the land in August, which the Bishop agreed to do, as long as there were a few stipulations: no footpaths crossing the land; the nearest path at least 180-200 feet away; housing to be more than 500 feet away; the road to be at least 100 feet away.

The parishioners remained unhappy and protested to the Bishop but were unable to sway him.

An objection was posted in the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette by the warden, R. H. Chamberlain, who wrote on behalf of the parishioners who had attended a meeting in the church vestry. In it, the view of the parishioners was that St David’s was being unduly burdened by the dead from other areas of the city. They felt that while they now accepted the use of Bury Meadows as a cholera burial ground, it was not fair that other parishes were not made to find their own burial grounds. It is clear, that many of the parishioners did not understand how the disease spread, with Chamberlain writing that the transportation and burial of people who had died from the disease could endanger the health and lives of the people of St David’s.