A local woman with an Interesting life.

Community researcher, Alison Allison

One of the first state certified midwives in Exeter was a local woman whose life was altered by a tragic case in which a baby in her care died. Her attempts to get her conviction overturned would cost her livelihood, home and last decades.

By the age of 15 Florence Annie Parkes had already moved out of her parents’ house in Regent St, Exeter and into 46 Northernhay Street in St David’s. She worked as a domestic servant to a 72 year old widow. By the age of 25 she had been promoted to a parlour maid and in 1901 was living in Kensington, London with another family headed by a widow. Meanwhile, her father had died and her mother, two younger brothers and lodgers were living in Little Silver also in St David’s.

Perhaps inspired by her mother, who was working as a sick nurse in 1901, Florence moved back to Exeter, and in 1904 was living close to the city’s hospital in Southernhay. Here she undertook a 3 month course in midwifery and was entered onto the newly established Central Roll of Midwives in 1905.

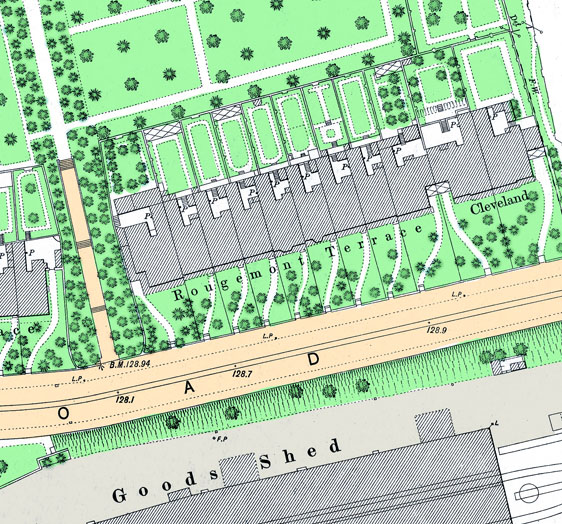

By 1917 she was leasing premises in Carlton Terrace, New North Road, and running a nursing home, ‘The Exeter’ for mothers and babies. She remained there until the estate of George Nind had her removed for non payment of rent in 1925. The collapse of her business and loss of her home followed an infamous case of infant death which was widely reported in the press at the time. After being turned out of her home penniless and with only a day’s notice, she was forced to walk to London to plead her case.

The case involved one of the young women in her care, Dorothy Gertrude Lee who gave birth to her son Alfred with Florence in attendance. Sadly, he died 7 weeks later, having seemingly been starved to death. Both Florence and Dorothy were charged with manslaughter and found guilty and sentenced to several months in prison. Dorothy would later go on to marry and have a daughter who was born in 1922. Florence was less lucky.

Continuing to protest her innocence she was forced to live in lodgings, moving between Torquay and London and taking on work as a nurse. In Torquay, she came across the anti-slavery campaigning wife of the then Home Secretary who persuaded her husband to review the evidence. Having seen signed statements and evidence which had not been submitted to the courts the first time round in 1917 he granted her a free pardon.

Following this pardon in 1935 she received £1,000 (the equivalent of £50,662.60 today) compensation and used some of the money for a trip to New York. On her return she lived in London for a while but by 1939 she was living in Torquay and described herself as a single retired nurse. She died in 1958 at Newton Abbott, aged 82.

The trial and the evidence.

The trial caused great excitement in Exeter in September 1917 and was widely reported in the local press. It lasted several days and the final verdict was delivered in the Guildhall in November 1917. By then enough detail had been reported to whip up a “mob of howling women” who surrounded Florence Parkes each time she left court. However, the judge did not consider this would have prejudiced the jury. Neither Florence nor Dorothy were well represented in court; one might speculate that many of the able bodied solicitors of the time were elsewhere deployed in 1917.

Florence was initially charged with neglect under the Children’s Act, but this was changed to a joint charge of manslaughter with Dorothy Lee. Her solicitor tried to separate Florence’s trial from Dorothy’s but this was refused even though her solicitor claimed it was without precedent to add a count which enlarged the offence she had been charged with.

The charge of manslaughter came about because of a confession Dorothy made to her own solicitor while Florence Parkes was also present. Dorothy told her solicitor (who later admitted he should have called for a police officer to hear the confession) that her mother did not want the child brought back to Torquay so she had intentionally ill fed the baby from the start and poured the milk away. If what she had confessed was true, it was a complete exoneration of Florence Parkes according to the Western Times.

We don’t know Alfred Lee’s birth weight; he was described by Florence Parkes as having been very thin from birth. At his death, he weighed only 4lbs 5 oz when his weight should have been closer to 8 lbs, yet Florence insisted that when she saw the baby in his bath the night before his death she didn’t notice anything unusual about him.

She was asked by the prosecution if she had not noticed he was gradually wasting away? Florence replied “No it never got any smaller; if it did I should have sent for a doctor.”Earlier she was asked if a doctor had ever been called in and Florence replied that “there was no necessity. If so I would have been the first to call a doctor”. Babies were routinely weighed, in order to improve infant mortality.

There was much discussion in court about whether Florence Parkes had given Dorothy Lee enough food to enable her to breast feed. There was also some suggestion that she had persuaded Dorothy to write a letter, after her baby’s death, saying she had been well cared for in the nursing home. However, Dorothy’s mother claimed she had received letters from Dorothy asking to come home, to Torquay, because she didn’t have enough to eat.

Florence’s co-defendant and her saviour

There was also suggestion in court that Florence Parkes had put Dorothy to work in the home.

Although certified midwives such as Florence Parkes were ‘supervised’ by 1917, her nursing home may not have been inspected in the way it would be today. The 1913 annual sanitary report for Exeter did not mention inspecting nursing homes but did record the number of certified midwives. Given the extraordinary events of 1917, it is unlikely that nursing home inspection would have been happening then.

Dorothy Gertrude Ellen Lee was born in 1899 and lived with her mother, also called Florence, and her father John, in Upton Road Torquay. Aged only 18, unmarried, and in the middle of the First World War, she fell pregnant.

The father of her baby was reported,at the time, to have been living in Exeter but was hard to get hold of and it was implied there were financial problems. Her mother, at the time of the baby’s birth and death, was a widow reliant on sewing work for money.

When Dorothy fell pregnant, her mother had no room for her, but she saw an advert for the Nursing Home run by Florence Parkes. After a conversation, in which she was said to have found Florence Parkes kind and anxious to help, an arrangement was made for Dorothy to give birth and stay there until a home could be found for the infant, and Dorothy was fit enough for work again.

Mrs Lee would pay Florence Parkes a reduced rate of ten shillings a week in instalments.

Mrs Lee claimed she had offered to pay for a doctor for the birth, but that Nurse Parkes had told her as a certified midwife she could take the case on.

Dorothy moved into the home in May 1917 and Alfred was born in June. By August, medical assistance was sought ‘for the first time’ as, one morning, Alfred had been found dead in bed with his mother. Following the trial, Dorothy was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to 9 months in prison. She was nineteen years old.

By 1922 she had returned to Torquay and married William Brooks. They had one daughter, Marjorie, that same year. In 1939 Marjorie was living with her mother and grandmother in Torquay.

Marjorie married in 1942 but sadly her husband died as a pilot in the Second World War before they had children. Dorothy died in 1982, aged 83 in Newton Abbott.

Viscountess Kathleen Simon was the second wife of the Home Secretary, (Sir John Simon), who pardoned Florence. Originally, also trained as a midwife, she was a widow with one son and had been employed to care for Sir John Simon’s three children, when he was also widowed. She went on to marry him and was renowned as a passionate anti-slavery campaigner. She was awarded an OBE for her work.

Lady Smith met Florence Parkes in Torquay. Florence had, by then, become involved with the spiritualist movement which was very popular after the Great War. She was told by the Reverend David Nash in a séance, that one day everything would be put right and people would crowd around her again. It might have been this faith that propelled her to continue to seek justice, as her friend and landlady Miss Jenkins suggested in the Western Morning News.