Community researcher – Carol Whitton

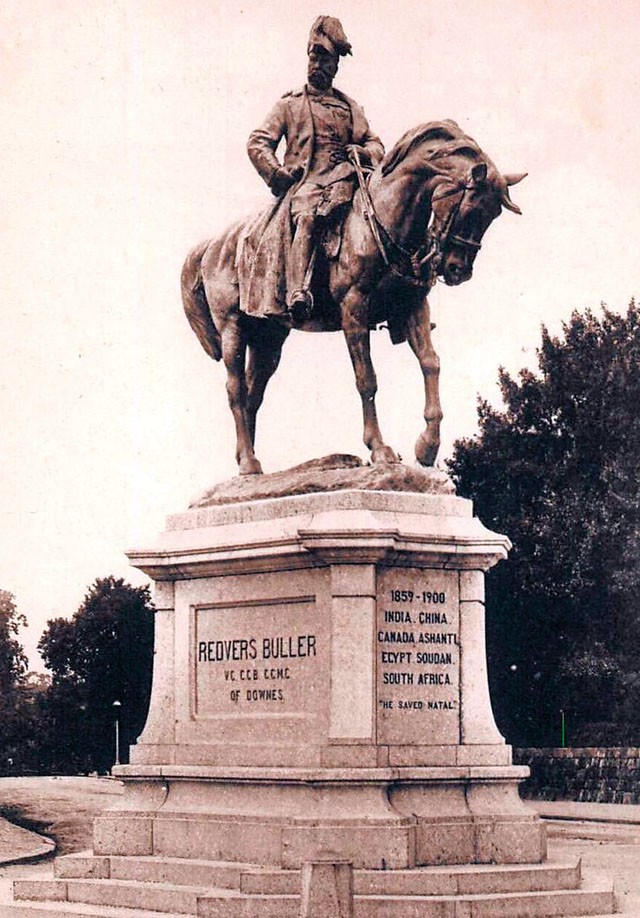

Since 1905, the approach to St David’s from the city centre has been dominated by the statue of General Redvers Buller astride his horse, Biffen, at the junction of Hele Road and New North Road.

This statue was unveiled on 6 September 1905 after 50,000 members of the public had subscribed to it. Sculpted by Adrian Jones, whose other works include the four horse chariot at Hyde Park Corner in London, the statue weighs four and a half tons and is mounted on a base of Cornish Granite weighing 35 tons. It was listed as a Building of Grade II historical interest on 29 January 1953. Sir Redvers was not himself an Exeter citizen. He had been born on the family estate of Downes near Crediton and he is buried in the Church of the Holy Cross in Crediton where the western side of the chancel arch forms an elaborate and highly visible monument to Buller’s exploits on the battlefield.

His most direct association with Exeter was through his father, who was Exeter’s Member of Parliament from 1830 to 1834 as had been several of his forebears.

The statue is not Exeter’s only association with General Buller. The City’s Civic regalia includes a sword in a jewelled scabbard originally presented to Buller by Lord Clinton in 1900 in honour of his military achievements. The sword is on permanent loan to the city and is housed in a display cabinet at the Guildhall. His association with the city is also preserved in street names, with both Redvers Road and Buller Road located just south of the Exe Bridges.

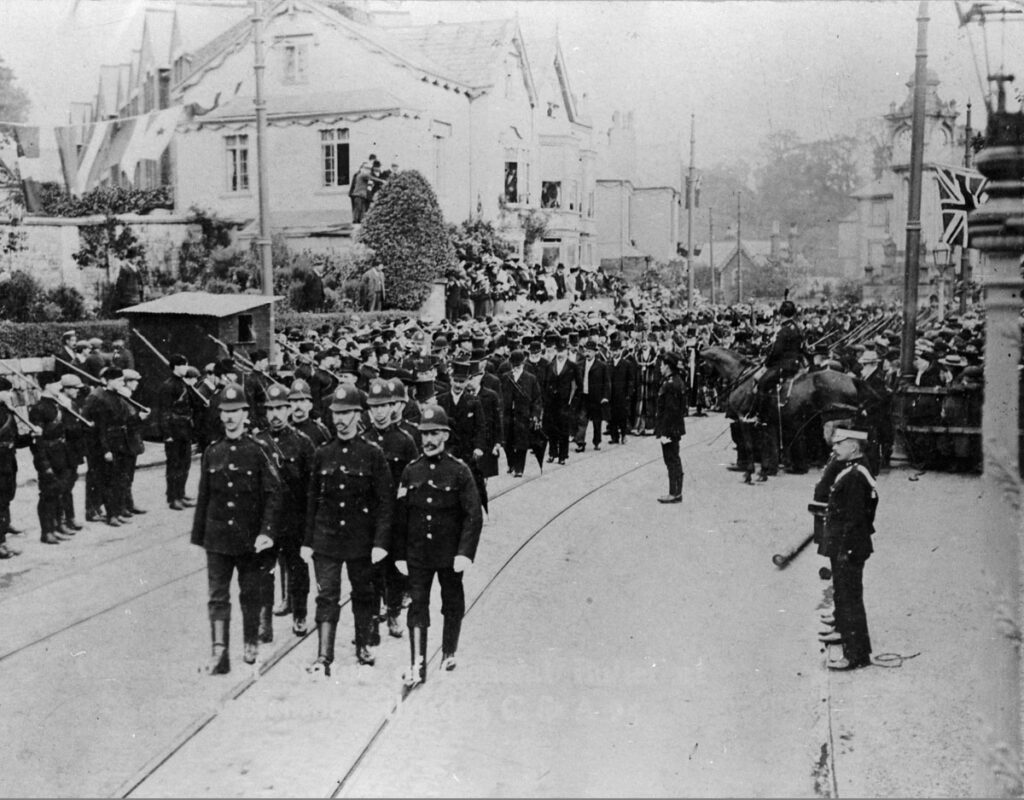

The day of the statue’s unveiling in 1905 was marked by widespread celebration, with the bells at the cathedral rung, a procession through the city accompanied by a military band, tea served in Bury Meadow for 500 army veterans, and a mass communal rendition of ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ by the crowd.

Yet whilst General Sir Redvers Buller was still being lauded in Exeter, he had long since lost favour in London having been dismissed from command in 1900. By the time the statue was unveiled he had lost the confidence of other commanders on the battlefield, was out of political favour with a new administration at Westminster and no longer had any prospect of attaining the coveted rank of commander in chief of the British Army.

Devon’s population persisted in taking this general to heart as a symbol of civic pride – perhaps because it allowed a strong expression of provincial defiance against the capital.

The last 50 years of the nineteenth century had seen Exeter’s role in the county diminish. In the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, Exeter had been a place where the rich and well to do of the county met and socialised. Exeter’s cloth was no longer being traded around the world as cities in the north of England took over as centres of manufacture and industry.

General Buller, however, became a figure Exonians could rally around with pride. Visitors flocked to the early picture show, known as a Myiorama, in the Victoria Hall in Queen Street to see images of the battle of Colenso with General Buller in the thick of the fray conveying a wounded soldier to safety. “For a brief spell, Exeter appeared once more as a provincial capital”. It could lay claim to a local hero who had achieved national and even global acclaim (Canada and Trinidad and Tobago also have their Buller Roads, as do cities within the UK as far afield as Brighton and Chesterfield).

It suited the Liberal party to support the groundswell of popular opinion to enhance their position against the Conservative party both locally and nationally, eventually winning a landslide victory in the general election of 1906 having already taken power locally from the traditional ruling landed gentry that formed the Conservative party of the time.

General Buller’s military career was played out in South Africa within the context of British and European Imperialistic ideologies, firstly in the Anglo- Zulu wars of 1879 and then in the Boer Wars of 1880-1881 and 1899-1902.

The inscription on the statue of ‘He saved Natal’ is a reflection of Buller’s strong association with the South African republic of Natal throughout his military career. It was from here that he launched the major offensive on the neighbouring Zulu nation in December 1878 during which he gained the Victoria Cross and it was to Natal that he returned as military commander when he was dismissed from his role as Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces in 1900. His final contribution to the war was to lead a successful march from Natal, which joined other forces to relieve the besieged town of Ladysmith in February 1900.

Buller arrived in South Africa on 31st October 1899 as an experienced and respected Commander but failed to live up to expectations with a disastrous attempt to cross the Tulego river to relieve Ladysmith in December 1899 which ended in retreat and the abandonment of many wounded men. Two further attempts to cross the river followed and also ended in retreat and heavy losses, with reports that he became known as Sir Reverse by his fellow officers. At this point, Buller was replaced as Commander in Chief by Lord Kitchener and Buller was demoted to the role of Commander of Natal.

Lord Kitchener, and not Buller, was in command when the British army developed its scorched earth policy to squash remaining Boer opposition which had gone underground following the relief of Mafeking.

The policy was intended to render the area incapable of providing sustenance to the Boer troops and included the use of horrific concentration camps that caused the death of many thousands of Boer women and children, as well as black South Africans until public outrage in Britain eventually put an end to the policy. There are no indications that Buller supported Lord Kitchener’s policy but accusations of his involvement linger.

In this global context, the Buller statue has associations with ideologies and policies which sit uncomfortably with the views of later generations. Whilst today’s citizens may feel the cause for that celebration is tarnished by association with the global imperialist attitudes of previous generations, the statue nevertheless provides a snapshot of a time when Exeter’s citizens came together to celebrate and to take pride in their city.

Memorial

As a student, I noticed him only for the traffic cones, one on the horse’s ear, one on his head. Then the unthinkable happened. A drunken lad scaling the horse’s back slipped. Tom Callaway. Dead at eighteen. Plants and photographs memorialised him. College students showed respect by going elsewhere for a smoke. In the evenings tea lights trembled in glasses. Today the pompous General sits there still. Plump and solid in his feathered hat, Entirely dead to history’s revisions. The horse, however, is breathing. The sculptor was an equine vet: his Boer War was horses. You can tell his hands adored the fetlock’s turn, the proud head’s dip, cared a good deal less for the haughty man with his hand on his hip. See how the horse’s mane and lifting tail are moving; see too how it’s muscles tense in duty. This is the horse’s long, laborious fate to bear the heaviness of history. Take our weight.